Ellen Freeman, a partner at Porter, Wright, Morris & Arthur LLP, recently co-moderated a panel discussion that addressed hiring international talent.

Hiring international talent is a critical piece of the company culture at Duolingo, the $700 million language learning app company founded by two immigrants.

In fact, most Pittsburgh technology companies agree that attracting and retaining talent from outside the U.S. is a vital part of the city’s progress.

Yet, Christine Raetsch, head of people at Duolingo, said it’s becoming more and more complicated to fill roles with international employees. Without an internal legal department, Raetsch said the work is “mindboggling.”

Last year, she spent a quarter of her hours working in the human resources role completing stacks of paperwork for immigration cases.

“The definition gets more and more narrow every time we submit,” Raetsch said. “..You have to be very precise in the language you choose. This is why you need a good attorney.”

That’s where experienced immigration lawyers like Eleanor Pelta, partner at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP, and Ellen Freeman, partner at Porter, Wright, Morris & Arthur LLP come in. The two co-moderated a panel discussion hosted by the Pittsburgh Technology Council recently to address hiring international talent with H-1B visas.

The H-1B visa program permits foreign-born people to live and work in the U.S. for a temporary period under the condition they have a sponsoring employer. The employer offering the job must apply for the visa.

The visa holder must hold a bachelor’s degree at minimum and work in a “specialty occupation,” which often translates into the expertise needed at tech companies.

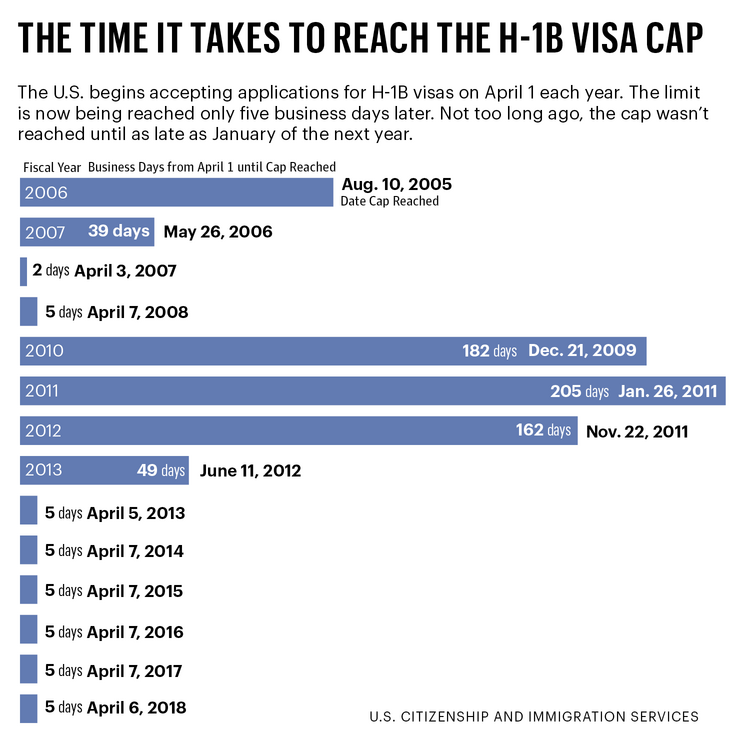

H-1B visas are capped at 85,000 each year, with 20,000 of those for foreign-born people with master’s degrees from the U.S. Out of a pool of over 200,000 applicants annually, those who receive H1-B visas are chosen by a lottery system.

The U.S. begins accepting applications on April 1 each year, and those who are given a visa may stay for a limit of six years before either returning home or applying for legal permanent residence through a qualifying relative or employer.

Katherine Huber, vice president of human resources at SDLC Partners, has

Business days from April 1 until cap reached been working to hire foreign-born talent for about eight years and said it’s essential for success.

“We just don’t have the local talent,” Huber said. “We are recruiting local and national, and (with) some of these more specialty skills, there just aren’t enough citizen workers.”

However, panelists agreed that under the Trump administration, the challenges of hiring international talent with H-1B visas have increased.

In April 2018, President Donald Trump signed the “Buy America, Hire American” executive order, which put an emphasis on hiring only the highest-skilled foreign workers or highest-paid beneficiaries and resulted in an increase in H-1B application denials and requests for evidence.

In August 2018, the president suspended the premium processing for H1-B petitions, a system used for foreign-born people already in the U.S. changing employers or switching to a new location with the same employer. The move drastically slowed down the processing of applications, and Pelta said she now sees people waiting on their pending applications for up to nine months.

Pelta estimates there are an unprecedented six million pending immigration filings in the U.S. right now.

“We call it an invisible wall,” she said. “It’s not the wall at the southern border yet, … but what we are seeing as immigration lawyers is that the petitions are taking longer and longer.”

Stefani Pashman, CEO of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, said Pittsburgh must take attract- ing international talent seriously in order to keep a competitive advantage in fields like artificial intelligence and robotics.

“We are not seeing a lot of population growth here, but we are seeing growth in foreign-born people,” Pashman said. “We have to continue that growth and accelerate it in a robust way.”

Laura Mullen, senior attorney at Argo AI, said when the self-driving company aims to hire foreign-born employees, it has to ensure it is choosing to fill roles that can stay open for that potentially nine months of waiting. Mullen said about 10 percent of its staff work under visas or green cards.

Raetsch reiterated this feeling, saying Duolingo put a policy change in place to make job offers even if the job has to be held for months while an employee transfers from another company.

“We never want to put the worker in the spot of losing their status,” Raetsch said. “That would be catastrophic.”

Carly Wilson, associate counsel at self-driving car company Aurora Innovation, along with Mullen and Huber, said they find themselves revisiting their company’s written policies around immigration and foreign workers much more frequently than they used to.

Despite the sometimes complicated system, Freeman said hiring foreign-born employees is worth Pittsburgh’s effort. In terms of cost, Freeman said the fees associated with applying for H1-B visas will essentially cost the same as hiring a recruiter.

Freeman was born in Ukraine and moved to Pittsburgh over 20 years ago. She encourages Pittsburgh’s business community to open up its networks to people with H-1B visas just getting settled in the city.

“I think there should be a concerted effort in Pittsburgh to take it to the next level and say you are welcome here, and this is your neighborhood too,” Freeman said.

Original Source: Bizjournals